Cobalt Strike Abuse And The Fight Against It

Just last week Microsoft’s DCU, Fortra and Health-ISAC moved to go legal and technical to disrupt cracked, legacy copies of Cobalt Strike and abused Microsoft software, which are been used by cybercriminals to distribute malware, including ransomware.

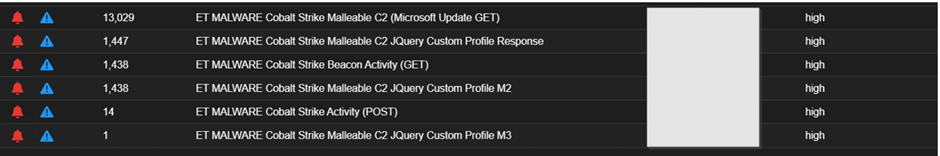

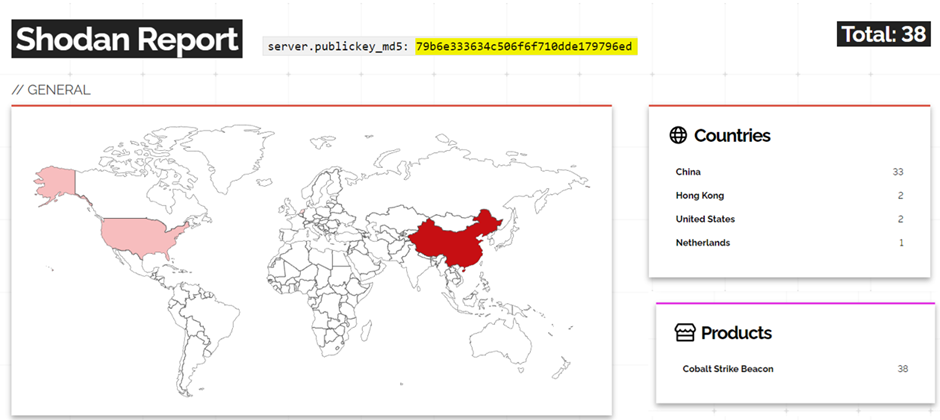

This week we are having a bunch of alerts coming from some facilities communicating with Cobalt Strike servers. Initial observation reveals the public key of one of the servers relates to 38 others in the wild. The abuse of this legitimate and popular post-exploitation tool has been found and reported in connection to several ransomware incidents; majorly those of high repute and impact.

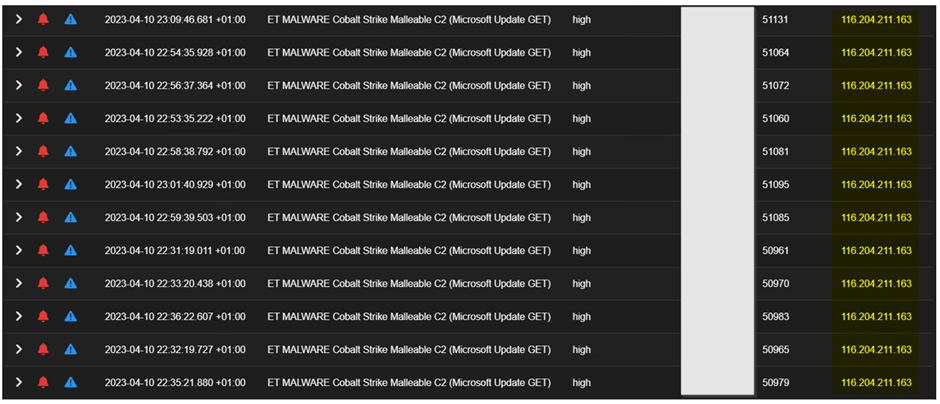

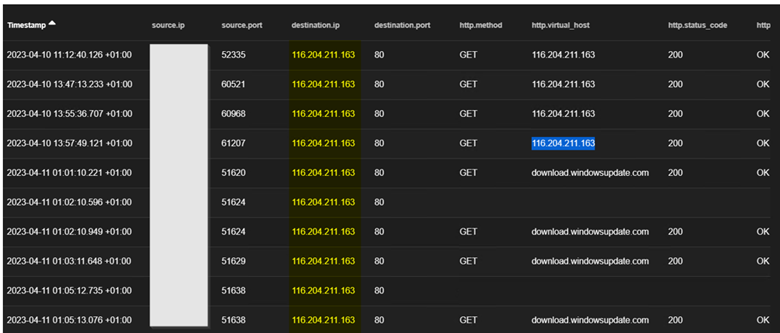

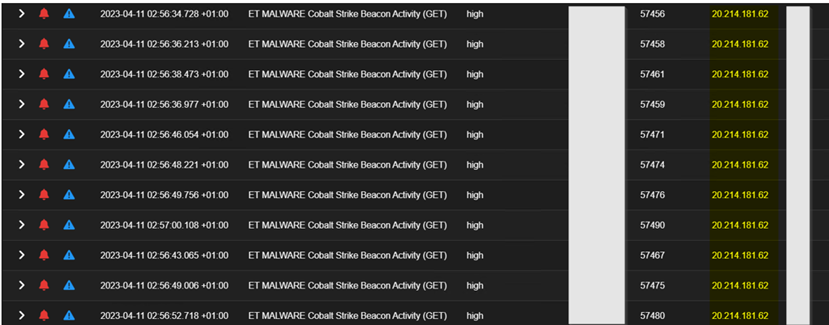

Drilling down on each of these aggregated alerts, you can see the communications as shown below.

It appears that around this time last year, a similar infection was uncovered relating to Cobalt Strike. But it now appears that the application of recommendations and fixes was not carried out as they should have; the possible reason for reoccurring of the incident. The first incident documented also appears to have happened alongside the time of the Bet9ja incident last year. Early detection was aided by notification of the Bet9ja incident back then and the commencement of a purple teaming engagement to find possible loopholes on our part.

Here are some of the questions that are coming to mind?

- Why always this time of the year?

- Or is there a time in the year an Op is targeted towards Nigeria?

- Could the attacker’s motivation be ransom-focus and financial-motivated? Cobalt Strike abuse found in notable ransomware cases.

- Why are IOCs appearing to be similar to the previous incident?

- Should we dig deeper into this attacking infrastructure to know more?

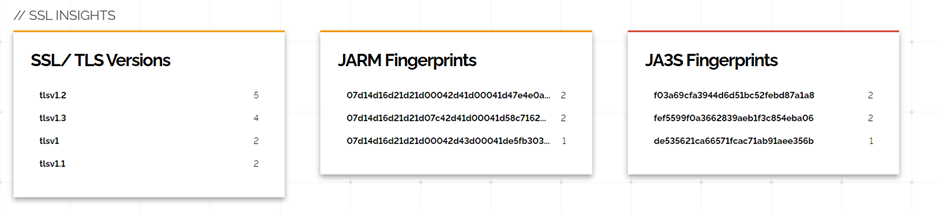

Going with the last question on the list, we started digging into this attacking infrastructure to see what we can learn and how connected they are to the previous incident. From the initial IoC discovered IoC – 116.204.211[.]163, 20.214.181[.]62, a public key associated with one of the servers was found to be related to 38 other servers in the wild as shown below; the majority were found to be hosted in China.

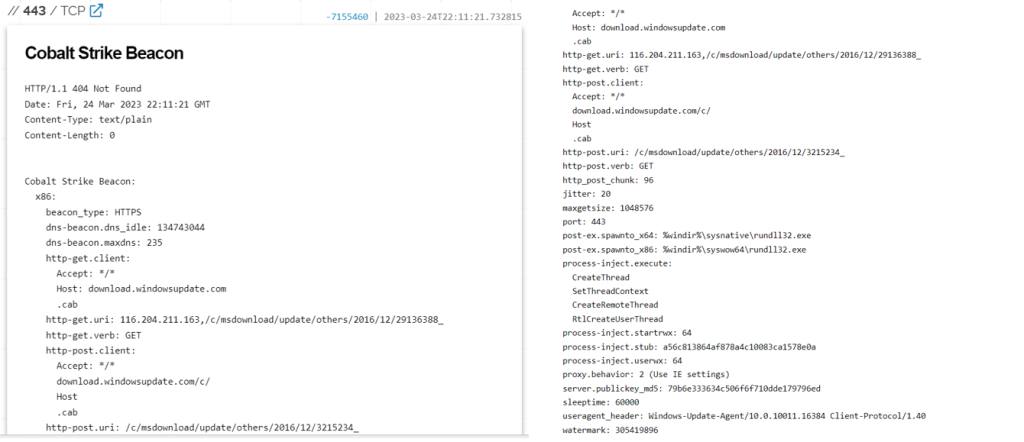

Here is the detail of the first server 116.204.211[.]163

http.uri /c/msdownload/update/others/2016/12/29136388_TqxXricvOOkwly_9Ob8TXWG0AeD0xANp2e-vVO9J89DVeKv821q7ugFnkEh50UZ6fcwinLA90emrTwMmR3SBi2OFd-yzHD1DaEDF0zKFqJVEDjQrVpWDKAjHkmjdlVi-JDzEAFaHOIWQvD01mczCHjQv0phGQw52fN1ktm-pws8[.]cab

http.useragent Windows-Update-Agent/10.0.10011.16384 Client-Protocol/1.40

http.version 1.1

http.virtual_host download.windowsupdate.com (detail in the Malleable Profile)

The image below confirms the server’s properties as it communicates with the facility

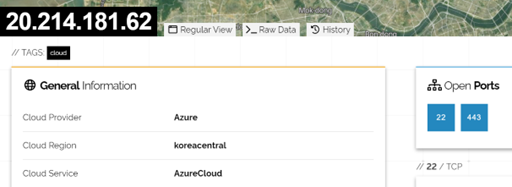

The second server 20.214.181[.]62 probably a redirection IP being leveraged by the attacker found here was found to be hosted on Azure cloud in the Koreacentral region as depicted below.

We believe that the threat groups leveraging these tools will want to revive their effort, as this fight continues to disrupt their operations. The fight won’t be a one-and-done but a continuous one requiring collaboration at all levels.

For other questions that we asked earlier, we recommend organizations and businesses in Nigeria and other African regions to keep staying proactive as this report shows signs of motivated threat groups hovering around our digital facilities.

For a proactive response to incidents and other cybersecurity services, you can always use our service at CyberPlural.

Leave a Reply